IAFOR celebrated the New Year by holding The 10th IAFOR International Conference on Education (IICE2025) and The 5th IAFOR International Conference on Arts & Humanities (IICAH2025) at the Hawai'i Convention Center, Honolulu, Hawaii, United States, from January 3-7. The conference was co-organised with the help of our local partner, the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, United States. The event attracted 483 delegates from 44 countries and leveraged the place and space of Hawaii to discuss global issues and international cooperation from a Pacific Islands’ perspective.

One of the central foci was the discussion on climate change, the number one threat to the Pacific Islands’ security. Transcending borders and cultures, climate change is a prime example of a global issue that requires international, intercultural, and interdisciplinary cooperation to solve. Education and academics in particular play an important role in keeping multilateral cooperation alive, especially in times of uncertainty regarding international cooperation paired with an increasingly destabilising global order. The local context of the Pacific Islands with their innate understanding of sustainability and resilience can inform the global community of opportunities, solutions, and actions that can be taken to tackle global problems affecting all of us.

Conference Report and Intelligence Briefing 2025 – Issue 3 – IICE/IICAH2025

Editor: Joseph Haldane

Authors: Melina Neophytou and Briar Pelletier

Published: March 17, 2025

ISSN: 2759-4939

In partnership with: The University of Hawai’i at Mānoa and the IAFOR Research Centre at the Osaka School of International Public Policy (OSIPP)

Subscribe and Stay Informed

Receive key insights directly to your inbox.

Stay informed of the latest developments in academia.

100% free to read, download and share.

Contents

Introduction

As 2025 begins, the world is being thrown into even more turmoil. With a new administration in the United States shaking up international trade, disrupting cooperation, and destabilising regions, global issues that plagued our planet for decades are becoming even harder to solve. One area in which this is conspicuously visible is climate change. Under President Trump’s leadership, the United States has once again motioned to withdraw from the Paris Agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, as well as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), and have ceased any financial commitments to global cooperation on climate change mitigation under the principle of ‘Putting America First in International Environmental Agreements’ (The White House, 2025). Furthermore, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has cut 90% of its foreign aid, leaving those dependent on these funds in a precarious position. While this diminishes the financial capacity to tackle common global threats, it also sends a negative signal to those who are committed to multilateral cooperation and mutual understanding. Further magnifying the rift among developed and developing countries, global issues such as climate change and social inclusion are becoming even harder to solve with international cooperation crumbling. The ones standing to lose the most from this are the already vulnerable and poor nations.

Hawaii and the Pacific Islands are a region that is particularly vulnerable to climate change. Despite climate change being the number one threat to the Pacific Islands’ security, the region also holds the key to a sustainable future and resilience, according to keynote speaker Dr Mary Hattori of the East-West Center, United States. As a Pacific Island-native from the Mariana Islands, she proudly stated that Pacific Islanders ‘are the first stewards of the ocean, so [their] knowledge is not only ancient, but [they] have thrived and [they] have been resilient for millennia’. She further asserted that ‘if people from other cultures can look at our models and adopt them to tackle their problems, then this is key for the survival of our people and our planet’.

IAFOR Chairman & CEO Dr Joseph Haldane delivered the Welcome Address at IICE/IICAH2025

Leveraging the place and space of Hawaii, The 10th IAFOR International Conference on Education (IICE2025) and Arts & Humanities (IICAH2025) in Hawaii addressed global issues such as climate change, social inclusion, Artificial Intelligence (AI), and international cooperation, giving local solutions and perspectives from the Pacific Islands. Various perspectives from plenary presenters aligned with the four themes identified by IAFOR as emerging issues over the next five years: (1) Humanity & Human Intelligence; (2) Technology & Artificial Intelligence; (3) Global Citizenship and Education for Peace; and (4) Leadership. With a focus on inclusion in leadership and decision-making, humanity’s innate capability of practicing sustainability and being one with nature, education for peaceful international cooperation, and the importance of technological innovation, the conference adhered to IAFOR’s mission of tackling pressing global challenges through a multitude of perspectives and angles.

With the Hawaiian conference being ‘a mix between East and West’, IAFOR’s Chairman & CEO, Dr Joseph Haldane, welcomed delegates to this contrastive and comparative laboratory that constitutes an IAFOR conference, in which the international, intercultural, and interdisciplinary perspectives illuminate that ‘there is a lot more that unites us instead of dividing us’. According to IAFOR’s President, Professor Jun Arima of the University of Tokyo, Japan, ‘climate change’, one of the conference’s central discussions, ‘is a prime example of an interdisciplinary issue that needs to be addressed with the cooperation of all countries and all professions across the world’. How do we engage with climate change and how do we teach it? ‘This is an ongoing interdisciplinary discussion that has been a constant over the past ten years’, said Dr Haldane in his welcome speech, opening the intellectual exchange of ideas on how to strengthen international cooperation on pressing global issues through education.

Opening with a perspective from the local context of the Pacific Islands, Dr Hattori highlighted threats and challenges that the Pacific Islands face, and opportunities that we can all seize, focusing on the actions that the Pacific Islands Development Project (PIDP) has taken to advance economic and social development in the region. Focusing on climate change, gender equality, social inclusion, and leadership development, she encouraged a deeper understanding of the local culture and international cooperation with various local agencies (Section 2).

IICE/IICAH2025 opened with a Cultural Presentation that welcomed delegates from 44 countries around the world to Hawaii

Following the illumination of Pacific Islands’ local realities, Professor Arima focused on a specific global issue that is facing a grim future due to crumbling international cooperation: climate change. Drawing from his experience attending the recent COP29, he provided insights about the outcome and discussed what implications recent developments in political administrations will have on the future of international cooperation (Section 3).

Flowing from this presentation, the floor was opened for delegates to discuss their views on climate change, willingness to pay higher taxes for climate change mitigation, and the role of education in raising awareness and shaping caring global citizens of the future. The Forum discussion, which combined global citizenship and the environment, was moderated by Professor Mike Menchaca of the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, United States, and Dr Melina Neophytou of IAFOR, Japan. It allowed delegates to share their insights and experiences with climate change education and express their views on climate change action in a one-hour moderated and interactive discussion (Section 4).

The programme included a Pre-Conference capacity-building workshop on AI in Education titled ‘Quality Courses Quickly: Using GenAI as a Course Design Assistant’. Led by Mr Daron Williams and Mr Dan Yaffe of Virginia Tech, United States, one of IAFOR’s global partner institutions, the facilitators assisted participants with demystifying GenAI and developing instructional materials while building a course during the session (Section 5). In a post-conference interview, Mr Williams and Mr Yaffe also offered insights on the future of the classroom and the implications of using AI in teaching and learning.

Ultimately, the conference attempted to raise awareness of the importance of international cooperation and academics leading discussions on contemporary global issues through education and interdisciplinary exchange in an era where not only multilateral cooperation is threatened, but also what it means to be human. ‘The more we see governments that abdicate [the belief in ideas, in communicating disagreements, and in seeking resolutions], the more Forums like IAFOR become important’, Dr Haldane concluded.

2. Global Issues and Local Solutions: A Pacific Islands Perspective to Sustainability

Humanity’s biggest problems are not confined within the borders of one particular country. Climate change is an example of a problem that is felt everywhere around the world and to which all countries contribute, but it affects some countries more than others. One area that is particularly affected by climate change is the Pacific Islands. Paradoxically, the Pacific Islands have practised sustainability for thousands of years, yet they are facing a disproportionate effect from climate change compared to more developed regions. These sustainable practices hold one of the keys to combating climate change, highlighting the importance of international cooperation and platforming developing countries to address global problems with local solutions. With the international political order being shaken up, opportunities are created for those countries with ‘unheard’ local solutions to global problems to take the lead and contribute to good and inclusive global governance. Leadership is, therefore, an essential skill that education must be cultivated in young students worldwide who are to become the leaders of tomorrow.

In line with IAFOR’s theme of Leadership, Dr Mary Hattori of the East-West Center, United States, highlighted the importance of international cooperation with the Pacific Islands in her keynote speech titled ‘Global Citizenship and Education for Peace: Threats & Opportunities from a Pacific Islands Perspective’. Focusing on the actions that the East-West Center (EWC), and specifically the Pacific Islands Development Project (PIDP), have taken to advance economic and social development in the Pacific Islands, she introduced the threats and challenges facing the region, but also the opportunities and actions that the international community can take to address these for the Pacific Islands and the worldwide collective.

Major threats and consequent priorities for the Pacific peoples, which come through founding documents like the 2050 Strategy for the Blue Pacific Continent, as well as the Pacific Leaders’ Gender Equality Declaration, include climate change, gender equality, social inclusion, and leadership development. Among them, climate change is considered the number one threat to the Pacific Islands’ security, for which solutions are hard to find since it requires the collaboration of all countries worldwide. The EWC effectively addresses the other three concerns by offering various programmes sponsored by the international community: it created the initiative ‘Women of the Waves’ to empower women in taking leadership roles in response to the decreasing number of women in the legislative seats in governing councils and parliaments across the South Pacific; it engages in leadership development funded by the government of Taiwan through the Pacific Islands Leadership Program, where it brings future leaders in connection with various leaders to establish networks for good governance; and it promotes social inclusion of marginalised Micronesian communities through programmes such as ‘Carrying Culture Micronesia’ teaching school teachers to get a different perspective on and change their attitude towards their students coming from Micronesia, and holding ‘Celebrate Micronesia’ festivals.

Dr Mary Hattori (right) speaks to IAFOR's Melina Neophytou (left) in an interview following her keynote presentation

Even though all these initiatives would not have been possible without assistance from the international community, in a post-conference interview, Dr Hattori cautioned against seeing the Pacific Islands as a victim in need of saving: ‘as opposed to taking the view that we need help from everybody else, I think the key to peace is realising that the Pacific Islands have things to teach: harmonious living, living as a collective, and supporting everyone – those are things that the Pacific Islands do innately, it is part of our culture’. As a Pacific Island-native from the Mariana Islands, she also proudly referred to the Pacific Islands’ ancestral wisdom on sustainability and resilience: ‘we are the first stewards of the ocean, so our knowledge is not only ancient, but we have thrived and we have been resilient for millennia. We have ancestral knowledge that is sustainable’. She encouraged first-time visitors to venture out of urban and tourist-oriented Hawaii and visit one of many native Hawaiian taro patches and farms, coconut nurseries, and fish ponds. ‘Many of these places welcome visitors and they teach about plant cultivation, the cultural and spiritual aspects of the land and the ocean, as well as things about the environment’, she explained.

Professor Mike Menchaca of the University of Hawai'i at Mānoa, United States, echoed Dr Hattori’s remarks about the importance of including the Pacific Islands in international negotiations, stating that there is a lot to learn about sustainability, the ecosystem, and being one with nature from the Pacific Islands. Conferences like those organised by IAFOR highlight ‘how understanding local cultural values and raising awareness can help global systems, global understanding, and global collaboration’, he explained. He commended IAFOR for ‘leveraging the local community and culture, and endeavouring to make sure that people learn about the history, the struggles, and the issues that may exist in the place they are at’.

Dr Hattori sees the Pacific as an emerging force in global politics, especially in areas such as the environment, agriculture, and sustainable tourism. ‘We are very humble people; pride is a sin in many Pacific islands, so we are not used to bragging about ourselves, but we are certainly invited to share. There are many life-affirming values that can really benefit Western society, and our partners and allies would be better-off and well-served by inviting us to share our expertise’, she shared in an interview. While the West struggles with issues of belonging and identity, a lot of solutions to these challenges can be found in the Pacific, according to her. However, this requires the West to allow the Global South to speak up. This was discussed extensively during a panel on ‘International and Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Global Citizenship in Times of Change and Crisis’ at IAFOR’s Paris Conference in 2024, where it was not clear whether the Global North is ready to relinquish some of its power to the Global South for the sake of inclusion. ‘I think this requires a level of cultural humility’, Dr Hattori said. ‘Any society that wants to survive must rely on external relationships’, she added. The next section explains why inclusion in international cooperation negotiations is not an easy endeavour.

3. Climate Change and The Future of International Cooperation

Since the 28th Conference of the Parties (COP28), the United Nations Convention on Climate Change in 2023, there has been a deep rift between developed and developing countries. While developed countries emphasise the reduction of emissions, developing countries are asking for more financial assistance from developed countries, calling for change. COP28 developed an agenda with a mixture of these two perspectives: climate change mitigation and increased financial assistance to developing countries. However, the parties have not yet been able to find a consensus on these two points. While multilateral negotiations on climate change are stalling, the cost for climate change mitigation constantly rises, having reached 4.3 trillion USD per year just to achieve the current SDGs (2030).

In his keynote presentation titled ‘Global Warming and International Institutions: Addressing Challenges Through Education and Action’, IAFOR’s President, Professor Jun Arima of the University of Tokyo, Japan, and Japanese Chief Negotiator for the Ad Hoc Working Group on Further Commitments for Annex I Parties under the Kyoto Protocol (AWG-KP) at COP14, 15, and 16, provided his insights about the outcome of the recent COP29 held in Baku, Azerbaijan, in November 2024. He also shared his prediction about the future of international cooperation on climate change and the role education plays in raising awareness and helping citizens make informed decisions about the costs of climate change mitigation.

Professor Arima explained how the single biggest issue at COP29 was agreeing on the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) on Climate Finance. Developed countries insisted on the expansion of the donor base to include countries such as China, whose economic situation has improved since the 1990s. They also asked to narrow down the target of recipients to especially vulnerable developing countries and small island states, effectively eliminating developing countries whose economy has grown in recent decades. ‘Developing countries did not like either proposition’, Professor Arima said, leading to a deep division between developed and developing countries.

Professor Jun Arima was Japanese Chief Negotiator for the Ad Hoc Working Group on Further Commitments for Annex I Parties under the Kyoto Protocol (AWG-KP) at COP14, 15, and 16

Additionally, with a new US administration likely to withdraw from international agreements on climate change mitigation, large financial contributions to this cause should not be expected. Similarly, key peace negotiations, such as those between Ukraine and Russia, may also be affected. ‘Climate change discussions rose after the end of the Cold War, and it is a testament to the fact that these discussions can only happen during times of peace’, Professor Arima explained. However, as we are entering a ‘new era of Cold War’ following the war in Ukraine, he predicted that international cooperation on any subject will be strained. As of March 2025, the United States have, indeed, withdrawn from international climate change negotiations, and peace negotiations with Ukraine have been suspended. With the United States unwilling to participate in climate change negotiations, contributions from Japan and Europe alone will not be enough to fill this vacuum, Professor Arima said. His realistic take on the future of international cooperation was that ‘if the huge transfer of funds to developing countries does not materialise, the ambitious energy transition will be “pie in the sky” (a pipe dream) and it will be clear to everyone that the already dead 1.5°C target is really dead’.

China is taking advantage of this situation to fill the power vacuum in climate change negotiations and challenge the global world order, Professor Arima added. While it rejects contributing to climate finance by developed countries, China offers financial assistance to developing countries through its bilateral cooperation. As the US withdraws from the Paris Agreement, China will be regarded as ‘the guardian of global climate change mitigation cooperation’, said Professor Arima. It is, indeed, not easy to navigate such complex global issues that affect each country differently. ‘The benefits of each country’s mitigation efforts are shared globally, but the economic cost is borne by each country. This is a perfect recipe for the prisoner’s dilemma. This is why climate change negotiations have made such little progress up to now’, Professor Arima explained.

The question, then, arises regarding who should shoulder the cost of climate change mitigation in the case that a consensus on climate finance cannot be reached. The Ukrainian war has elevated the priority of energy security in many countries, and energy prices have soared. Naturally, the general public does not like the rising cost of living. However, without this rising cost of energy, governments cannot sustain their climate change mitigation policies.

This is why the role of education is of utmost importance. According to Professor Arima, ‘people should be more informed about climate change, the energy reality, and economic consequences of more ambitious climate change mitigation actions. Currently, they tend to believe that climate action has no price tag, but it actually costs. With proper understanding of the implications of climate change actions, they can make an informed decision’. While he did not propose that education is the key to solving the deadlock in climate change negotiations, it can pave a new way to move forward: on the one hand, it can raise awareness and understanding of issues related to climate change, and on the other hand, it can drive technological innovation. According to Professor Arima, we should devote more time to developing innovative technologies. If technology becomes readily available and economically viable, climate change mitigation efforts will not cost people a lot of money so as to sacrifice their economic prosperity. For him, innovation is the key to solving a complex negotiation problem.

Professor Jun Arima (right) speaks to IAFOR's Melina Neophytou (left) in an interview following his keynote presentation

Evidently, the focus on discussing climate change elevates the importance of education and technology. While it is hard to find a consensus among competing political interests, it is much easier to find solutions in training people’s minds and capabilities. Teaching people to care about the environment and others, to inform themselves without falling prey to disinformation and bias, and redirecting their and education’s knowledge-making towards a public cause will harvest much better results than any international negotiation. IAFOR’s themes of Human and Human Intelligence, Technology and Artificial Intelligence, and Global Citizenship and Education for Peace each touch upon this issue, framing the discussion of climate change in such a way that solutions and next steps can be found that do not discriminate between developed and developing countries.

So, if the 1.5°C target is ‘dead’ and cooperation is stalling, what are our immediate next steps? Though he tends to be a pessimist about international politics, Professor Arima is a cautious optimist about humans’ capacity to deal with various problems through technological innovation. ‘I said that the 1.5°C goal is dead, but I don’t think the climate change mitigation actions are finished’ he explained. Many countries are still taking climate mitigation actions. These may not result in realising the 1.5°C target, but it is certain that the global community remains actively moving towards carbon neutrality. ‘It may not be 2050 - it could be somewhere between 2050 and 2100 - but still, it is worth doing’, he positively added.

In a post-conference interview, he concluded with some remarks to those for whom the term ‘crisis’ may not be enough to compel them to action:

For those who argue that it’s too late to act, I would like to say that it is not too late. Whatever actions you can take now would make a difference in the future. Even though we cannot achieve the 1.5°C goals, what you are doing now is not in vain. I think that deserves applause. For those who say we are now facing a “crisis” or a climate catastrophe, I would like to say that there is no word such as “crisis” in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, so don’t dramatise it too much. It is definitely a problem, but it is not an existential problem. We can cope with this problem with proper handling, for example with innovation and technology development. For those who argue that climate change is a hoax, climate change is happening. Of course, how much is caused by anthropogenic activities and how much by natural phenomena could be debatable, but the correlation between human activity and greenhouse gas emissions is almost certain, with a 95% probability. So, you should not call it a hoax.

4. Global Citizenship and Climate Change: Perspectives from the IAFOR Community

Following Professor Arima’s presentation, The Forum, IAFOR’s intellectual caravan, opened the floor for delegates to discuss their views on climate change, willingness to pay higher taxes for climate change mitigation, and the role of education in raising awareness and shaping caring global citizens of the future. Within a one-hour moderated discussion session titled ‘Global Citizenship and the Environment: Engagement and Action’, moderators Professor Mike Menchaca of the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, United States, and Dr Melina Neophytou of IAFOR, Japan, asked delegates to share their opinions and insights on three main questions: (1) Are you willing to pay more for climate change? (2) Who should shoulder the cost of climate change mitigation? (3) Can climate change action be taught? Participants had reserved opinions about the responsibility of climate change mitigation, as well as the possibility of action against climate change being teachable, considering that it would have to fundamentally change one’s behaviour and values.

The first question inquiring about participants’ willingness to pay taxes for climate change mitigation yielded mixed results: 42% said ‘yes’, 38% said ‘no’, and 20% said ‘it depends’. Prompting them to elaborate on their answers, those who said ‘it depends’ were more proactive in sharing their opinions. While the amount of tax and transparency issues (‘will the tax money go to its intended cause or for a politician’s expensive car?’) were some obvious reservations, others shared their insights on cost-benefit, privilege, and the dangers of imposing a conditional carbon price.

Climate change is an externality to some benefits that a society has enjoyed for a long time. Development involves cost and benefit. If I have a reason to believe that I enjoyed more of the outcome of what led to climate change, I’d be willing to pay. But, if I have a reason to believe – and it is statistically proven – that I did not enjoy the benefit much, then of course I would not be willing to pay. Those who contribute more to climate change should be willing to pay more.

- A delegate on the issue of cost-benefit

I don’t have an actual answer to your question, because I think the first piece is a question of privilege. Who has the privilege to make these types of choices? If you have the privilege, you probably have the economic power, and that would make a difference in how you respond to this question.

- A delegate on the issue of privilege

Climate change is a global problem. The ideal solution is to have a common carbon price all over the world. This is actually not impossible to consider. On one hand, there could be a high carbon price for certain areas, and there could be a lower carbon price or no carbon price in other areas. This could cause carbon leakage from a high carbon price region to a lower one, such as relocation of the production place. In the end, the global emissions may not decrease. This is the most difficult part of this problem. In order to address this problem partially, the European Union is currently considering a carbon border tariff, [which means] imposing a carbon tariff on imported goods from countries such as China and India. Those countries are naturally against this proposal, saying that this is a restriction of trade under the name of climate change mitigation. That could lead to a trade war. This is why I voted for “it depends”. I’m ready to pay to some extent, but if, for example, Japan’s carbon mitigation cost is too high compared to countries like China, then that could cause carbon leakage from Japan to China. That would not be in the interest of Japan.

- Professor Arima on the dangers of imposing a conditional carbon price

The second question asked delegates who should be responsible for shouldering the rising costs of climate change mitigation. Participants shared nuanced understandings of contributions to climate change versus responsibility of mitigation, and the mitigation-adaptation dilemma. A clear theme emerging from this discussion is the notion of trade-off.

We are all paying for the disaster response. Wherever the disaster happens, those costs are borne primarily locally. It is often Indigenous communities that are adversely affected. When we talk about the cost, we have to keep in mind that this is not entirely a voluntary thing on our part. Some of us may have the privilege of voluntarily paying more, but we are all going to end up paying the costs of the disasters that happen repeatedly because we refuse to do anything about it. Then, it becomes a question of “what are you willing to pay for?” Do you want to keep paying a trillion dollars here in the US to maintain a military to try to keep the price of energy low? Or do you want to pay higher taxes to try and mitigate the problem of higher prices, or do you want to pay for the disasters? To a great extent, this is not voluntary – we will end up paying regardless.

- A delegate on the issue of involuntary payment as a responsibility

I do disaster research and community response in Australia. We have a problem with insurance in Australia that whole towns that are now getting postcodes are not going to be insured, end of story. There is no nuance, there is nothing. What the insurance companies are now doing is picking up on initiatives to help people prepare their houses. The insurance companies are the ones doing it. The government is trying to do it, but now it’s late to come on board. If you think about climate change, in Australia we are told to drive less or to recycle. We as the community are not the polluters. And yet, we get guilted into thinking that we are the problem as individual households. The bigger problem actually is being diverted from agriculture, which is the biggest polluter. There is a lot of misdirection. You are pointing at this person here and blaming them. We are looking at the wrong places sometimes.

- A delegate on the issue of misdirecting responsibility

To respond to these insights, Professor Arima clearly defined the issue as one of a trade-off between mitigation and adaptation:

Climate finance for mitigation and adaptation needs to be discussed here. Mitigation tends to be more expensive than adaptation. With adaptation, you spend a certain amount of money and can feel the benefit from that adaptation finance directly because the adaptation problem tends to be local. But mitigation is a global problem. So, even though you spend a huge amount of money on reducing emissions, the total impact globally is very minimal. Currently, about 70-80% of the total climate finance goes to mitigation rather than adaptation. We need to rebalance climate finance.

Responding to the issue of disaster response, he also added that:

‘It is very difficult to attribute disaster to climate change. Looking at the sixth assessment report of the IPCC, there is a clear interrelation between anthropogenic activities and greenhouse gas emissions and the rising global temperature. But in regards to the frequency of heavy rain or drought, according to the report, scientific certainty is much lower compared with the correlation between anthropogenic activity and higher temperatures. So, we are definitely causing a higher temperature, but the scientific confidence about us causing heavy rain is questionable’.

The last question inquired about whether participants think that climate change action can be taught. The majority of delegates (65%) answered yes, while only 7% said no, and about one-third answered ‘maybe’. Intrigued by the possible reasons for answering that climate change action cannot be taught, the moderators asked those who answered negatively to elaborate on why they thought so. There was a clear lack of belief in the ability to change someone’s attitude towards climate change action, as action (or behaviour) presupposes the existence of according values and beliefs. Changing one’s behaviour is, therefore, extremely difficult.

I think practices can be taught, but practices come from beliefs, and beliefs come from ideologies. At least in the US, we are encountering ideological differences as a society that are very difficult to break into. If you couple that with what is allowed and what is not allowed in K-12 schooling, there are tremendous challenges with answering just “yes” to this question.

- A delegate on the issue of changing ideologies

We can’t change the minds of people, we change their hearts. We think that we are dealing with people’s minds and rational choices and that we are dealing with a rational public, but when you look at the information space, we are not dealing with rational people. We are not rational; we have our own stories, we’re the heroes of our own narratives, and we live in little bubbles where we have people agreeing with us on social media. If you present something that is too hard and that you don’t identify with and don’t feel emotionally good about, then what are you doing? So, when we say “taught”, how would you do that? Would you teach someone to feel different?

- A delegate on the issue of rationality versus emotion

You cannot teach somebody to believe in something. It’s quite a challenging task. Can you teach people to understand that climate change is actually happening? Maybe that’s possible. But can you teach them to take action against climate change? I think that’s a pretty difficult task, at least in this generation. With the generational change, maybe we need a new generation to come that will understand and appreciate the environment.

- A delegate on the issue of teaching climate change action

Professor Mike Menchaca of the University of Hawai'i at Manoa moderated The Forum discussion

Countering this view, a delegate shared that we have seen such ideological changes and changes in belief before by colonial powers. Therefore, it is possible to teach climate change action through a change of belief and behaviour:

We need to look at beliefs. People can believe in something because they don’t have other alternatives. Depending on the environment you’ve been brought up in, you will tend to believe whatever transpires over there. But as you move from your environment to another place, you receive alternative information and you begin to renew your mind about what is happening in your society and whether to accept it or not. Let me go back to colonialism. In Africa, we had a God before Christianity came. But because white people brought Christian beliefs to us, we now tend to believe in Christianity more than our traditional religion, because they have been teaching us. In the same way, climate change can be taught to renew people’s traditional beliefs.

- A delegate on the issue of religious belief

The Forum discussions reflected the broader challenges facing international climate negotiations, particularly the tensions between economic costs, policy decisions, and public engagement. Delegates discussed the responsibility of climate finance, the feasibility of teaching climate action, and the trade-offs between mitigation and adaptation – issues that echo the deadlock Professor Arima witnessed at COP29. The Forum discussion reinforced the fact that international cooperation remains uncertain, especially in today’s political landscape. As Professor Arima suggested, fostering a deeper public understanding of climate realities can drive more informed decision-making, while advancements in technology can make mitigation efforts more practical and less economically burdensome. Many participants at the Forum had opposing views to this as they placed more emphasis on passing the responsibility of climate finance to those who enjoyed the trade-off between economic prosperity and climate change. This is not always a comparison between states, but also between industries. Though the path to carbon neutrality remains long and uncertain, the discussions at The Forum reaffirmed that progress, however incremental, is still possible – and necessary. It is essential that we hone in on what makes us human: the ability to care, to believe in ideas, inclusion, and empathy, and to fight for a common cause – and to recognise that this can be achieved through education and the advancement of technology.

5. Capacity-Building Programme

As part of IAFOR’s efforts to give back to our community through capacity building, the IICE/IICAH2025 conference provided a Pre-Conference Workshop on ‘Quality Courses Quickly: Using GenAI as a Course Design Assistant’. Recognised as one of the most pressing issues affecting the world today, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is being adopted quite slowly by educational institutions. In order to ‘help faculty demystify GenAI’, Mr Daron Williams and Mr Dan Yaffe of Virginia Tech, United States, a global partner of IAFOR, showcased how AI can be used to generate instructional materials and relevant coursework.

‘AI is here, and it is here to stay’ said Mr Yaffe in a post-conference interview. ‘Educators don’t have to use it, but they have to teach their students how to use it responsibly’. Mr Williams added that ‘I don’t know what the future holds, but I do know that folks who know how to use AI and understand what it does well and what it doesn’t do well will be the best-prepared to meet the future demands’. Asked about what kind of knowledge we can create with the help of AI, Mr Williams answered that ‘a lot of people within their disciplines will have great knowledge that they bring to the table, but being able to have this conversational chat-partner that helps you fill in some of the gaps and be able to communicate different topics better or perhaps to different audiences, we will be able to create any kind of knowledge using GenAI as a partner. The sky's the limit’. These perspectives speak to the relevance of AI discussions, to the importance of AI in interdisciplinary discussions and knowledge creation, and to why it is important to continuously re-skill educators.

6. The IAFOR Undergraduate Research Symposium (IURS)

IAFOR also held The IAFOR Undergraduate Research Symposium (IURS) in Hawaii, where 9 undergraduate students participated. IURS runs alongside the select IAFOR international conferences where participation is open to academics with a Master’s degree and above. IURS is specifically designed for undergraduate students to present their original research with support, training, and capacity-building development sessions. The symposium is held over two days, with an online day explaining how to formulate thoughts, structure presentations in ways that are engaging and easy to understand, and communicate intentions with maximum clarity and impact. The second day is then held onsite during an IAFOR conference and focuses on the hard skills that allow students to operate as effective communicators during presentations. These techniques are invaluable in academic, business, and everyday contexts, and they allow students to convey their ideas in ways that leave strong impressions on their audience. IURS helps undergraduate students make an academic contribution while also developing career skills in the process.

Professor Grant Black, IAFOR’s Vice-President and Professor at Chuo University, Japan, acted as the main facilitator of the symposium. ‘Regardless of your plans to pursue a career in academia or not, if you have the ability to communicate your ideas concisely, you are going to do well in life because that is a highly valued skill in any setting’, Professor Black said. In Hawaii, he instructed undergraduate students on the main elements of a presentation, and prompted the students to present their posters to regular conference delegates. IURS participants later on expressed that they had learnt a lot from the engagement with more senior academics, and that the symposium reinforced their desire to continue and excel in their academic careers. Networking and making new friends among their peers was a common point of appreciation from the event.

Participants were particularly grateful for the preparation session before the actual presentation. ‘The symposium was really helpful because at the beginning, I had a hard time putting words together’ said Mr Clarence Maor Barzilay, an undergraduate student from the Philippines. ‘I was trying to make my research sound a bit flashy and diving into the technical parts of it. But then I learnt that it is much easier and efficient for the person listening to make it very simple and just have them ask you questions’. Ms Jakayla Davis from the United States also said that ‘with public speaking, I am usually a little bit nervous. But because of that pre-session we had, we were able to be prepared and go over some tips for breaking down how to present and how to make it more natural. I think because of that, it went really smoothly and I wasn’t thinking too much during the actual presentation’. Ms Chi Que Pham, an undergraduate student from Vietnam, particularly talked about the struggle of being concise and efficient when explaining research:

One struggle that we all had in common in this group of undergraduates was that it’s not that our ideas were not fleshed out or that the arguments were not there. It was more about how do we get them more concise and accessible, and how to avoid academic jargon. We are going to go out into the world, we will become teachers, engineers, or researchers. So, we need to know how to communicate and how to let everyone know that our research matters. You can’t use academic jargon to get through that.

Interdisciplinarity was another point that undergraduate participants valued a lot at this symposium and conference. This cohort’s research topics varied greatly: from psychology, media and censorship, AI in education, and aviation equity to health science, their presentations may have seemed an odd inclusion at an education and arts & humanities conference. However, participants were particularly excited about this. ‘I actually got a range of delegates who were interested in how I can teach and educate people on the matters I am interested about, which is something I always thought about but I never got an answer to from people in my field’, said Ms Pham, speaking to education’s portrayal as the ultimate interdiscipline. Ms Zanyah Rae Williams, an undergraduate student from the United States, also said that ‘one thing that this conference has taught me is that there are so many interconnected factors that should be included in research’.

‘It is incredibly important to support undergraduate students because they are the future’, said IAFOR’s CEO, Dr Haldane. ‘Capacity-building is important, so we want to provide students with the communicative tools to communicate their ideas. It is an incredible opportunity for undergraduates to communicate with other delegates from all over the world not only about their research, but also about what is happening within their countries’. IURS follows IAFOR’s principles of international, intercultural, and interdisciplinary exchange while helping undergraduate students to get on board the academic journey. IAFOR hopes to see those undergraduate students succeed in their future academic endeavours and welcome them back to an IAFOR conference in the future as proper delegates.

IAFOR Vice-President Professor Grant Black (left) and Chairman & CEO Dr Joseph Haldane (right) at the IICE/IICAH2025 Welcome Reception

7. Networking Events & Cultural Programme

Holding a conference in Hawaii ‘is not only beneficial for the tourism industry, but it is also an opportunity for local, native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders to showcase their understanding and their cultural worldview, and what others can learn from that worldview’ said Conference Programme Committee member Professor Michael Menchaca. IAFOR’s Conference Networking & Cultural Events aim to provide spaces and events where conference delegates from around the world can engage with each other, as well as local artisans, their culture, and their knowledge. As Professor Menchaca explained further, ‘understanding local cultural values and awareness can help global systems, global understanding, and global connection’. The Hawaii Conference Programme featured three spaces designed to foster this idea: the Conference Welcome Reception at the Hawaiian Convention Center, a Hawaiian Music and Hula Dance Cultural Event, and the Conference Dinner at Roy’s Waikiki.

Welcome Reception

The Welcome Reception closed out the pre-conference programme on Friday, January 3 in the Children’s Courtyard within the Hawai’i Convention Center. The Welcome Reception is designed to allot time within the busy conference schedule for delegates to relax, connect, and network. Facilitating spaces for delegates at all levels of their careers can form long-lasting connections within the IAFOR network and is a key aspect to our conference planning. The Welcome Reception is a free event, open to everyone registered for the conference.

Conference Dinner

The Conference Dinner was hosted on the evening of Saturday, January 4 at Roy’s Waikiki, and remains a favourite event in IAFOR’s Conference Programme in Hawaii. Delegates enjoyed a course menu curated by Japanese-American celebrity chef, Roy Yamaguchi, one of the founding members of the Hawaii Regional Cuisine movement. The restaurant is located inside Waikiki Beach Walk, an open-air luxury shopping complex which sits beside Waikiki Bay.

The Conference Dinner is an exclusive event where plenary speakers, IAFOR Executives, esteemed guests, and delegates can dine together and connect at spectacular venues. Each iteration of the Conference Dinner offers a chance for conference attendees to explore and experience the unique cultures and locations in which IAFOR conferences are held.

Conference Cultural Event: E Hele Mai a Hula: A Hawaiian Music and Dance Workshop

Robyn Kuraoka, a hula instructor, joined us in leading ‘“E Hele Mai a Hula”: A Hawaiian Music and Dance Workshop’ on Friday, January 3. As the daughter of community leader and Living Treasure of Hawaii, ‘Auntie’ Carolee Nishi, she followed her mother’s footsteps and passed down her ancestral knowledge on Hawaiian culture to her own teenage daughter, who was also present during the workshop. The workshop introduced delegates to the movement and music of the Hula, a native dance of Hawaii. Ms Kuraoka led delegates through learning basic chords and melodies on the ukulele, and steps of the Hula dance. She and her troupe of dancers and musicians performed again on Saturday, January 4, for a Cultural Presentation during the plenary programme.

Auntie Nishi herself joined the Cultural Presentation during the plenary programme, performing traditional Hawaiian songs and ukulele melodies for the audience. Auntie Nishi was designated a Living Treasure of Hawaii in 2020 and has been dancing and teaching for over fifty years, performing on stages across Hawaii and the world throughout her career, including Disneyland, United States, and the 1970 Osaka World’s Fair, Japan. Her warm instruction stems from her many years welcoming and guiding students of all ages and backgrounds, perfect for IAFOR’s global network. One delegate commented that the Hula Cultural Event was ‘fantastic… I had never seen this at another conference before’. IAFOR is fortunate to have Auntie Nishi and Ms Kuraoka join us again to share their craft, as their contributions to our conference programme are well-loved by attendees.

8. Conclusion

Hawaii, an island-country with a rich and contentious history that has played an outsized role in international affairs, has welcomed IAFOR for the tenth consecutive year to host the IICE/IICAH2025 conference as a bridge between East and West. As a region that can teach us a lot about sustainability and the environment, the Pacific Islands are a fitting backdrop against which we can discuss global issues such as climate change – a focal point of this conference. The plenary presentations at this conference have highlighted the significance of the Pacific Islands as a valued partner in international cooperation, urging both the Pacific to take a leading position and offer their perspectives, while also calling on the West to create space for their voices to be heard.

How do we engage with climate change and how do we teach it? This was the central question posed at this conference, which was discussed through the lenses of all four themes identified by IAFOR as emerging in the next five years. Dr Mary Hattori of the East-West Center, United States, discussed the Pacific Islands’ perspective on climate change and other social issues, speaking on the themes of Leadership and Humanity & Human Intelligence as a way to promote local sustainable solutions to global issues. Professor Jun Arima of the University of Tokyo talked about international cooperation on climate change, tackling a global issue from various perspectives: Leadership, Education for Peace, and Technology & Artificial Intelligence. With the message that developing and developed countries must act together and education informing citizens about making sound decisions on climate change, he urged educators to raise awareness of the situation and focus on the advancement of innovative technologies. The Forum discussions on climate change and education, part of IAFOR’s Global Citizenship series, allowed delegates to share their own perspectives on climate change and education. Throughout the academic programme, the connection between the local and the global was undeniable.

As with all IAFOR conferences, the IICE/IICAH conference programme is an opportunity for local, native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders to showcase their understanding and their cultural worldview, and what others can learn from that worldview. According to Dr Hattori, the Pacific Islands are an emerging force in the international political arena and should, therefore, have more confidence in speaking up. ‘There are many life-affirming values that can really benefit Western society, and our partners and allies would be better-off and well-served by inviting us to share our expertise’, she stated. With many global issues being exacerbated by the uncertain and de-stabilising political climate of 2025, international cooperation with multi-stakeholders has become a necessity. In the course of the next year and leading up to the next conference in Hawaii, IAFOR is looking forward to drawing in more Pacific perspectives and voices from an extended Pacific region, which can include all North and South Pacific Islands and stretch from New Zealand to the Alaskan region.

‘We need people from other countries, from other disciplines, and from different professions’, noted IAFOR’s Chairman & CEO, Dr Joseph Haldane, in his welcome address. There is much more that unites us than divides us, since some of the biggest problems we face are not confined within the borders of one country. These large-scale problems, such as climate change or AI, require all of us to come together. An important part of being at a conference is that we are engaging in discourse, discussion, and disagreement using our voices, and not our fists or weapons. This is exactly where the power of education lies in fostering peace and respect. According to Dr Haldane, ‘the more we see governments that abdicate [the belief in ideas, in communicating disagreements, and in seeking resolutions], the more Forums like IAFOR become more important’. IAFOR will continue to provide a safe space for international, intercultural, and interdisciplinary exchange of ideas for a more peaceful future.

Subscribe and Stay Informed

Receive key insights directly to your inbox.

Stay informed of the latest developments in academia.

100% free to read, download and share.

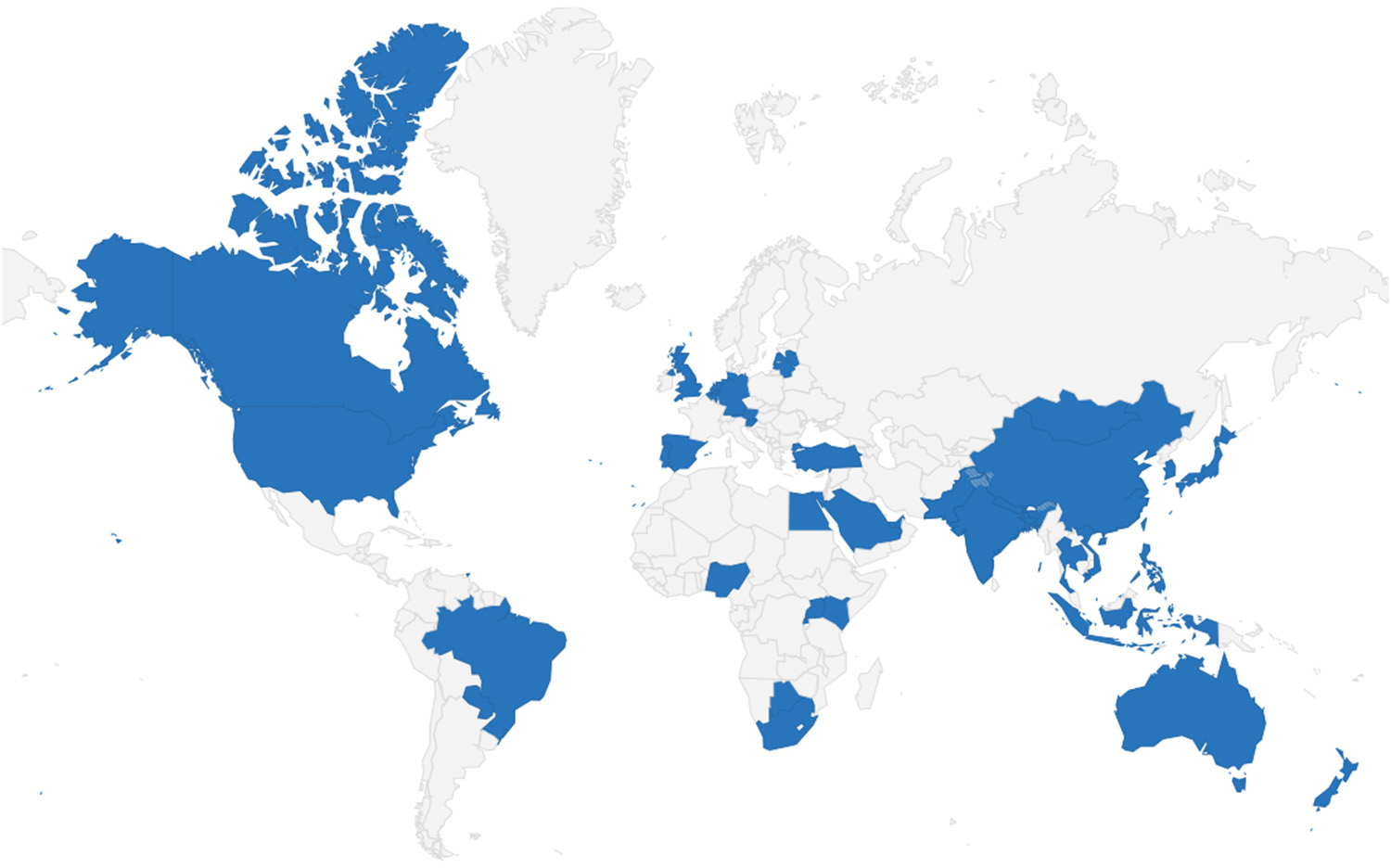

IICE/IICAH2025 Key Statistics

Delegate World Map & Country Breakdown

Total Number of Attendees: 483

Total Number of Countries Represented: 44

| Country | Count |

|---|---|

| United States | 170 |

| Japan | 72 |

| Canada | 64 |

| South Korea | 29 |

| Taiwan | 17 |

| Philippines | 11 |

| China | 10 |

| South Africa | 10 |

| United Kingdom | 7 |

| Hong Kong | 6 |

| India | 6 |

| Rwanda | 6 |

| Saudi Arabia | 6 |

| Australia | 5 |

| Slovenia | 5 |

| Spain | 5 |

| Germany | 4 |

| Mongolia | 4 |

| Pakistan | 4 |

| Thailand | 4 |

| Vietnam | 4 |

| Austria | 3 |

| Country | Count |

|---|---|

| Indonesia | 3 |

| New Zealand | 3 |

| Singapore | 3 |

| Bangladesh | 2 |

| Egypt | 2 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 2 |

| Belgium | 1 |

| Botswana | 1 |

| Brazil | 1 |

| Brunei | 1 |

| Kenya | 1 |

| Latvia | 1 |

| Lithuania | 1 |

| Malta | 1 |

| Nepal | 1 |

| Netherlands | 1 |

| Nigeria | 1 |

| Paraguay | 1 |

| Portugal | 1 |

| Turkey | 1 |

| Uganda | 1 |

| United Arab Emirates | 1 |

Subscribe and Stay Informed

Receive key insights directly to your inbox.

Stay informed of the latest developments in academia.

100% free to read, download and share.