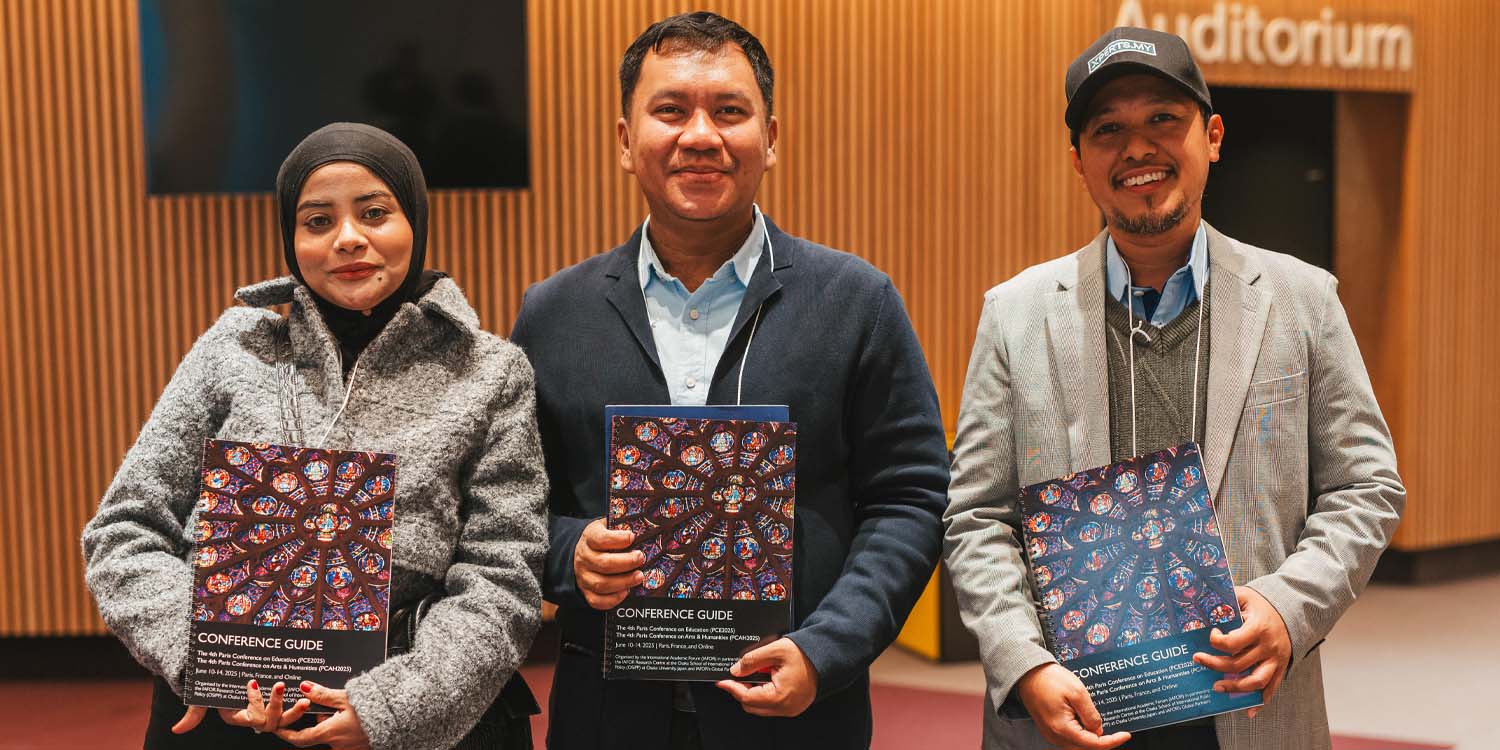

The 4th Paris Conference on Education (PCE2025) and The 4th Paris Conference on Arts & Humanities (PCAH2025) invited participants to engage with how we can rethink education and culture in a polarised world increasingly focused on defence, security, and the commercial value of ‘softpower’. The conference, hosted at the Sorbonne University International Conference Center, welcomed some 500 participants from 80 countries and over 400 institutions worldwide.

With this year marking the 80th anniversary of UNESCO’s constitution, UNESCO Assistant Director General for Education Dr Stefania Giannini welcomed this year’s delegates in a special open address urging the audience to invest in a more imaginative and humanistic education that is able to address today’s global challenges. Keynote speeches and panels at the conference emphasised the importance of education and culture in preserving the intrinsic qualities that make us human, including our shared history and values, expressed in intellectual cooperation and exchanges, cultural monuments, literary and artistic works, and our relationship to nature.

Conference Report and Intelligence Briefing 2025 – Issue 7 – PCE/PCAH2025

Editor: Joseph Haldane

Authors: Melina Neophytou and Briar Pelletier

Published: September 5, 2025

ISSN: 2759-4939

In partnership with: The IAFOR Research Centre at the Osaka School of International Public Policy (OSIPP)

Subscribe and Stay Informed

Receive key insights directly to your inbox.

Stay informed of the latest developments in academia.

100% free to read, download and share.

Contents

Introduction

Historically rooted in the 19th and 20th centuries, efforts to establish mutual understanding among nations through cultural diplomacy have led educators, artists, and merchants on voyages across continents, opening up avenues to global trade, free movement, and technological advancement. Marco Polo’s famous journey into the unknown left behind a legacy that, in Ambassador Sabbatini’s words, ‘reminds us that building bridges between people and nations is especially vital in times of geopolitical tension’. Today, these geopolitical tensions, disruptive technologies, demographic changes, and economic instability threaten international cooperation and peace around the world. National interests overshadow socio-economic development, and budget cuts to education to finance defence and security are compromising century-long efforts at internationalisation, cross-cultural exchange, and understanding. In these turbulent times, when intellectual cooperation is sidelined by national interests, education plays an even more important role in keeping the global community together.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, UNESCO established the pillars of education, science, and culture as guarantors for peace and societal rebuilding. This investment into people and knowledge, or culture and education, referred to today as ‘soft power’, needs to be reimagined, according to UNESCO Assistant Director General for Education, Dr Stefania Giannini. It is important to bring human imagination back to the centre of what we do and celebrate in education, especially at a time where technology and AI are isolating us and universities are becoming increasingly transactional. Tolerance, respect, decency, and patience are ‘things we need to relearn in a world that is always in a hurry,’ added IAFOR’s Executive Vice-President and Provost, Professor Anne Boddington.

This rethinking and relearning extends beyond education to all realms of intercultural communication. Cultural heritage, previously seen as the pride of a nation, a symbol of ancient wisdom and knowledge, and an inspiration for artistic and literary masterpieces, is now increasingly viewed as a commodity and source of income. However, the business of cultural diplomacy is also what ensures heritage sites are preserved and visited by millions of people every year. The reconstruction of Notre-Dame in Paris, despite some national pressure against its reconstruction, is an example of how history, the arts, the sacred, and nature are still valued today. ‘We need to be careful that transactional value does not overshadow this intrinsic value of cultural heritage, as is the case today with mass tourism’, said Japanese Permanent Ambassador to UNESCO, Ambassador Takehiro Kano. Balancing the commercial and intrinsic value of culture and education is an ever-more-important question we need to think deeply about today.

This year marks the 80th anniversary of the constitution of UNESCO, which was adopted right at the end of the Second World War. Its famous preamble, ‘Since wars begin in the minds of men, it is in the minds of men that the defences of peace must be constructed’, echoes even stronger today. The 4th Paris Conference on Education (PCE2025) and The 4th Paris Conference on Arts & Humanities (PCAH2025) invited speakers and panellists to discuss how we can education and culture can be rethought in a polarised world that focuses increasingly on defence and the commercial value of ‘softpower’.

Opening the conference with a special address, UNESCO Assistant-Director General for Education, Dr Stefania Giannini, urged us to invest in a more imaginative and humanistic education capable of addressing today’s global challenges. To achieve this, universities must remain international, intercultural, and interdisciplinary spaces of free inquiry and critical thinking (Section 2).

Vice-President for Europe and International Affairs of the Institut Polytechnique de Paris, France, Christopher Cripps, outlined the opportunities and challenges of internationalising higher education in France, demonstrating that education and research transcend borders even when politics divides (Section 3).

In a panel discussing educational cooperation in times of crisis, IAFOR’s Provost Professor Anne Boddington, Professor Donald E. Hall of Binghamton University, United States, and Mr Cripps defined the term ‘crisis’ as something not historically unique to this time or equally felt in all parts of the world. From their perspectives as senior academic leaders, they tackled questions of past mistakes, present opportunities and challenges for education and students alike, and future expectations of educational collaboration and student mobility (Section 3).

Encouraged by Dr Giannini’s and Professor Boddington’s insistence on defending interdisciplinarity, and inspired by the ACAH/ACCS/ACSS2025 Conference’s plenary discussions in May, the Forum discussion in Paris allowed participants to discuss the challenges that interdisciplinary research and collaboration face today (Section 4). In a one-hour moderated discussion, IAFOR’s Vice-President, Professor Grant Black of Chuo University, Japan, and IAFOR’s Academic Operations Manager, Dr Melina Neophytou, guided participants in sharing their experiences with interdisciplinary research in their institutions and countries. The discussion showed that, while every institution, nation, and culture faces different challenges when engaging in interdisciplinary education and research, interdisciplinarity remains difficult worldwide.

The culture and cultural diplomacy section of the conference was addressed first by Professor Jean-Michel Leniaud of the École Pratique des Hautes Études, France, who spoke about Notre-Dame as a symbol of sacredness, historical continuity, ritual practice, and artistic achievement. Its reconstruction after the 2019 fire, and the record-high visitor numbers following its reopening, is a testament to the intrinsic value of culture, which he saw as a combination of history, religion, nationalism, art, literature, and nature (Section 5).

In his keynote speech, Ambassador Paolo Sabbatini of the World Sinology Center, China, referenced Marco Polo’s ‘journey into the unknown’ and the legacy he left behind for international cultural and educational cooperation. Emphasising people-to-people diplomacy and the fact that cultural diplomacy is practiced by everybody daily, he argued that building bridges between people and nations is increasingly important in times of polarisation and division (Section 6).

This was followed by a panel on education and cultural diplomacy for peace. Dr Charlotte Faucher of the University of Bristol, United Kingdom, the Japanese Ambassador to UNESCO, Takehiro Kano, Professor Frédéric Ramel of Sciences Po, France, and Ambassador Sabbatini, traced the origins of cultural diplomacy, and discussed the connections between civil society, educators, artists, merchants, and governmental actors in intercultural communication, the importance of preserving cultural heritage and repatriation, as well as the commercial value of cultural diplomacy (Section 6).

The conference also featured two roundtables (Section 8), a cultural presentation by local singer-songwriter Sophie Leliwa performed the legendary chansons of Barbara, one of France’s most beloved folk singer-songwriters (Section 9), and various networking opportunities such as the Welcome Reception and the Conference Dinner (Section 9). The performance of Barbara’s chansons, a genre inscribed by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage (la chanson française), allowed delegates to engage with a shared understanding of history, memory, and the lived experiences of women in postwar Europe. Introducing another intangible cultural heritage inscribed by UNESCO, the Conference Dinner offered a taste of French cuisine to our delegates, allowing them to engage with a shared, and now global, gastronomic heritage. Such events are included in every IAFOR conference programme, as musical performances and food have proven time and again to provide ways to engage with our shared cultural heritage, and that food, music, and people-to-people diplomacy provide powerful ways for international, intercultural, and interdisciplinary exchange.

The next sections explore the academic and cultural programme in detail.

2. Challenging Times Require Challenging Education

The 1990s were a time when internationalisation flourished in Europe. In his welcome speech, IAFOR’s Chairman & CEO, Dr Joseph Haldane, recalled a more positive and peaceful time of celebrating the international and intercultural. As he retraced his memory of being an 18-year-old university student in Paris in the 1990s, he explained that the ‘international’ was not something that needed to be defended at that time. Today, internationalisation is perceived by many as something strange or wrong, and engaging with the foreign has become more difficult. However, according to Dr Haldane, ‘international engagement is incredibly important at times when we may feel that our governments don’t properly represent us; they are sometimes inward-looking, nationalistic, and authoritarian. This is not what IAFOR is about. We are about international engagement in a positive way.’

IAFOR Chairman & CEO Dr Joseph Haldane delivered the Welcome Address at PCE/PCAH2025.

However, the world today is facing global challenges that are changing the socio-economic and political landscape within which education and intercultural communication operate. Geopolitical tensions, economic instability, demographic changes, climate change, and disruptive technologies urge us to rethink the purpose of education and culture. ‘Meaningful human interaction must be the foundation for everything we do in education,’ Dr Giannini stated. She added that ‘universities are where ideas are tested, where values are debated and where futures are imagined and shaped. Throughout history, they have been spaces for free inquiry, critical thinking, freedom of speech, public debate, standing as bridges between the past and the future.’ As such, educational institutions need to remain free, inquisitive and responsive to global challenges, promoting the international, intercultural and interdisciplinary, and protecting it from those who ‘question very much about it.’

3. Rehumanising Education

France, much like the rest of Europe, started working towards the internationalisation of education intensively in the 1990s, when it became a national and institutional focus backed by government support, policy frameworks, and stakeholders. Back then, internationalisation was synonymous with student mobility, and was often seen more as a punishment, explained Vice-President for Europe and International Affairs of the Institut Polytechnique de Paris, France, Christopher Cripps. In his keynote presentation titled ‘Internationalization of Higher Education in France: Challenges and Opportunities’, he outlined France’s efforts to internationalise its higher education system, effectively making a case for a changed perception of ‘internationalisation’ in 2025. ‘What does it mean to truly internationalise higher education in 2025, when the world around us is becoming more fragmented, more fragile, and more fearful?’ he asked. According to him, internationalisation is no longer just about mobility, but about mindset, mission, and mutual respect. Students nowadays are pursuing mobility opportunities with great interest, revealing a change in societal and cultural mindset, which the French education system is quickly catching up on.

Despite the growing interest of students and faculty in internationalising education, socio-economic and political realities are currently hindering international cooperation efforts. While students increasingly demand to study abroad, hurdles such as geopolitical tensions, budget cuts in education and research, and their own economic situations, do not allow them to do so. This may be perceived by many as a crisis, but according to IAFOR’s Provost, Professor Anne Boddington, this is nothing new. During a panel discussion on ‘Cooperation in Times of Crisis: Education, Leadership and Global Citizenship’, moderator Professor Donald E. Hall of Binghamton University, United States, asked whether we are in a time of global crisis. Professor Boddington clarified that the times are felt differently in different parts of the world. It is a fact that developing countries have been fighting these obstacles in higher education for decades. Student mobility or funds for education and research were not readily available to them as it was for students from developed countries. ‘It is just that now it is affecting people that it hasn’t affected for a long time,’ said Professor Boddington. ‘The challenging thing is who can afford to stand up to a government. It’s about challenging things that have not been challenged in this context before,’ she continued.

So, what exactly needs to be challenged? The panel echoed Dr Giannini’s call to bring back human imagination to the core of education. According to Professor Boddington, education has become highly transactional, so the challenge is how to maintain a sense of socialisation, both between university partnerships and between students, and also across disciplines. University partnerships, often established through Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs), are meaningless if there are no person-to-person collaborations or if they fail to produce a meaningful outcome.

‘Partnerships are not just a PR tool,’ Mr Cripps stated. In terms of students, we need to make sure that their experiences and their future are meaningful too. Whether it is about studying abroad, writing a PhD dissertation, or making career choices, Professor Boddington suggested that educators and mentors push students to think about essential questions: why did they choose a certain country to study abroad, where do they position themselves in the world, what questions do they want to ask through their research, and what difference do they want to make in the world?

Interdisciplinarity is another challenge we need to prepare our students for. ‘What does interdisciplinary education mean, and how do we teach people to be generous and welcoming to other fields? We need to be conscious about the silos we are creating around disciplines,’ Professor Boddington said. Adding to Dr Giannini’s statement that interdisciplinarity is important because it carries with it principles of internationalism, inter-independence, and innovation, she acknowledged that interdisciplinarity and collaboration are difficult to engage with:

Within the context of IAFOR, which is doing a lot of interdisciplinary collaboration, I will say this: interdisciplinarity and collaboration are hard things to do. Conferences are an interesting place where we can see this. How many people go to listen to other people’s presentations, struggle to speak in a different language, and how many people have the tolerance and the patience to listen harder in order to understand?

Professor Boddington’s final message to educational leaders is to bring the human element back to the core of education: ‘One of the things I think we’ve lost in our impatience with the world sometimes is the tolerance, the decency, the respect, the resilience to listen to another person. This is one of the things that we need to re-learn in a world that is always in a hurry.’

4. Defending Interdisciplinarity: Insights from The Forum

At the PCE/PCAH2025 Conference, the one-hour moderated Forum discussion session among delegates tackled the challenge of engaging in interdisciplinary research and collaboration, which both Dr Giannini and Professor Boddington found difficult to engage with. Inspired by the discussions at the ACAH/ACCS/ACSS2025 Conference in May 2025 in Tokyo, where peace, war, and conflict studies became the topic of debate around disciplinary silos between seemingly identical fields, the conference in Paris carried out a Forum discussion on ‘Cooperating in Difficult Times: Global Citizenship and Interdisciplinarity’. Moderator Dr Melina Neophytou of IAFOR together with IAFOR’s Vice President Professor Grant Black of Chuo University, Japan, as a respondent, asked the audience about challenges of interdisciplinarity. The session was so engaging that IAFOR has decided to continue the discussion about solutions to practicing interdisciplinarity effectively in a ‘Part II’ format at the ECE/ECAH/EGen2025 Conference in London in July 2025 (report forthcoming).

Interdisciplinary research emerged as both a strong aspiration and a persistent challenge among the delegates. While most participants either already engage in cross-disciplinary work (67%) or expressed interest in doing so (33%), institutional support remains uneven. Challenges to interdisciplinary research and collaboration included uneven formal policies, limited funding, informal encouragement, and disciplinary silos. Heavy workloads, the risk of being seen as generalists rather than specialists, funding structures tied to specific departments, and the undervaluing of interdisciplinary outputs in promotion and publication processes were also common barriers to engaging in interdisciplinary work.

Professor Grant Black of Chuo University, Japan, served as respondent for the PCE/PCAH2025 Forum session.

Some delegates emphasised the challenge of being perceived as a ‘jack of all trades, master of none’ within academia if they engaged in interdisciplinary research. Generalisation versus expertise is often perceived as a negative, and it is hard to communicate between disciplines without insulting their depth:

When I was studying at university, they were offering a programme in International Relations, which was a combination of history, political science, and languages. The students were coming out of university, educated a little bit in each field, but not a specialist in anything. So, it was seen as a ‘failure’ because they were not properly educated in any discipline. That degree is now gone.

– A delegate from Cambodia

We recently got a funded project where we [computer scientists] were working with the department of Social Sciences on how we can achieve digital inclusion for people with disabilities. Part of doing this is to get published and to get promotions. The problem in India is that this is neither considered research in education nor in computer science. Education people will say, ‘this is too shallow’, and computer scientists will say, ‘this has nothing to do with theoretical computer algorithms'.

– A delegate from India

My research integrates different fields: Education, Communication, Music, and I work with people with disabilities. The challenge for me is how do I present all this information? Who am I talking to? Because I can be too technical as a musician, but a linguist might not understand, and vice versa. The challenge is to mediate all these areas and try to sound compelling in presenting this work to everyone.

– A delegate from Colombia

I think it’s very hard for faculty, depending on their faculty load and how much free time they have to learn another subject, especially if they are trying to get published and gain more recognition in their field. You are either called to be an expert in something or a jack of all trades.

– A delegate from Turkey

The ‘silo mindset’ is a direct cause of this challenge, further complicating engagement in interdisciplinary research and collaboration. Specifically, one delegate mentioned that:

One challenge is that some people have that ‘silo’ mindset: when you are an expert in your field, you cannot imagine that someone who is outside of your field has anything of value to add. But, in fact, having an outside perspective and having various perspectives sheds new light on the way we do and see things. I think some people see the value behind that, but not everybody does. Lots of people I’ve worked with have said, ‘Thanks for that perspective, but you don’t know my field.’ And I think that’s a shame.

– A delegate from Canada

Another delegate commended IAFOR’s work in promoting interdisciplinarity within an academic landscape that generally tends to avoid it:

One challenge is bringing people of different disciplines together in one room like this. I want to commend IAFOR for doing this. Many conferences are general meetings for medical science, electrical engineering etc. They don’t want to bring on board other people from other disciplines. But this educational initiative brings people from different disciplines together to discuss and look at how they can collaborate or work together. So, thank you.

– A delegate from Kenya, working in Japan

Budgetary constraints, closely linked to institutional fragmentation in some countries, were another challenge identified by participants. A poll conducted during the session revealed that only 50% of participants’ affiliated institutions encouraged interdisciplinary research and supported it through formal policies, funding, and study programmes, while 29% encouraged it informally, without institutional infrastructure or dedicated funding. For 13% of participants, their institutions primarily focus on discipline-specific research, providing no support for interdisciplinary collaboration at all.

The problem we have in the Philippines is how we approach research. It is fragmented. Interdisciplinary research is encouraged, but it lacks institutional support. The funds are given per department. So if I work in the Department of Theology, I can only get the funding allocated to my department. In order to collaborate with other departments, I have to have really good friends from other departments.

– A delegate from the Philippines

In Colombia, every government proposal is for only one discipline: you have funding for music, arts, or mathematics. So, everything is separated. If you want to integrate different disciplines, you will probably be disqualified… If you want to link with other departments or universities, they will say, ‘Yeah, but it’s not convenient for us. We cannot have research on music, because we need that money for computer science.’ Most of the interdisciplinary research we do is ‘underground’ and a ‘hush’ thing. Also, in Colombia, there are different ministries for culture, science, and sports [the Ministry of Cultures, Arts, and Knowledges; the Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation; and the Ministry of Sports]. These categories don’t ever mix. It is difficult to impossible to get funding or cross over to other departments.

– A delegate from Colombia

However, one delegate mentioned that budgetary constraints in their institution in fact unintentionally promote faculty positions with interdisciplinary requirements:

Because of budgetary constraints, my university does not advertise positions as purely Management or Finance anymore, but they are grouping the disciplines for that position. Now we are seeing that you have to have a background in Strategy, in Ethics, in Finance to be shortlisted for the position. This is a new trend because of budgetary constraints.

– A delegate from Trinidad and Tobago

Asked about the challenge of bringing disciplines together in terms of methodologies, a poll conducted during the session revealed that the majority of respondents (66%) thought it’s possible for disciplines to find common ground with only partial methodological alignment and careful contextualisation. 21% of respondents thought it is possible for disciplines to coexist and adopt each others' methods and language fully, while 13% thought it is completely impossible for methods to be translated meaningfully across disciplines.

Despite these results, one delegate mentioned that interdisciplinarity is crucial to address global challenges.

Topics such as climate change are very complex and cannot be addressed by one discipline. I think a lot of problem-based thinking and learning is going to require more interdisciplinary thinking going forward.

– A delegate from Sweden

One of the goals of interdisciplinarity is impact and problem solving. It’s one of our motivations for doing it. So, when we are thinking about interdisciplinarity, we should also be thinking about what it means. What does it mean across sectors? What does it mean in terms of action research? Who are our participants? How do we work across sectors with NPOs and NGOs?

– A delegate from the United States

In closing, one delegate’s comment offered a picture of interdisciplinarity today:

I was a bit confused at the start of this session, but it made me realise that I’m extremely lucky. Coming from an Economics background, I feel like I was exposed to interdisciplinarity my whole academic career. In economics, you have the usual suspects of maths and statistics, but you also have history and consumer psychology. So, I was a bit confused as to why there is not more interdisciplinary research in academia. How is this still an issue? I feel lucky to be an economist.

– A delegate from Serbia

The challenges of engaging with interdisciplinarity are clear to most academics and educators. It is a matter of convincing institutions and policymakers to enact changes and promote interdisciplinary research and collaboration. Part II of this Forum discussion, held at the IAFOR conference in London, takes the debate one step further and looks at solutions to these challenges.

5. Cultural Heritage as a Unifying Force: The Example of Notre Dame

Turbulent times and times of crisis have always come and gone. In 18th-century France, the overthrow of the Ancien Régime and the events of the French Revolution caused social disorder and a series of violent events, later defined as the Reign of Terror. During those violent times, there was one place in Paris that became an essential point of convergence, a place of calm and peace: Notre-Dame. Today, Notre-Dame is a UNESCO-designated World Heritage Site that attracts millions of visitors from all over the world. In his welcome speech, Professor Georges Depeyrot of the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS), France, acknowledged the importance of Notre-Dame, jokingly saying that ‘if you wanted to visit the Roland-Garros 2025 (the French Open tennis tournament), it’s too late; if you wanted to visit the Olympic Games, it’s also too late; but you [still] have enough time to visit one of the most important monuments in French history, Notre-Dame’.

What does cultural heritage mean? What exactly have we inherited from Notre-Dame, and why does it attract so many people today? These are questions that Professor Jean-Michel Leniaud of the École Pratique des Hautes Études, France, explored in his keynote presentation titled ‘Notre Dame de Paris: Holy Place, Sacred Edifice, and World Heritage Site.’

Today, when we look at Notre-Dame, we find ourselves in a place containing ‘the anamnesis of history, the memory of history that constantly returns to mind, and the magnetic influence of the sacred place’, said Professor Leniaud. For him, four essential elements converge to create a paradigm of ‘heritage’, making Notre-Dame the sacred place it is today.

First, due to its geomorphological aspect, situated between a mountain, a desert, a river, and a man-made bridge, it is a place where nature and humans come together, defying time. Second, it is an ancient sacred site, which holds traces of both paganism and Christianity, spanning a 900-year period of ancient wisdom and faith. Third, it is a meeting place between God, religion, civil power, and the nation. All major national events have taken place in Notre-Dame, including royal weddings and Napoleon’s coronation, giving the monument a ritual significance. According to Professor Leniaud, visiting Notre-Dame stems from ‘a desire to master this long span of history.’ Finally, the fourth element is the Cathedral’s artistic character. From its Gothic and Baroque architectural elements to its influence on literary works written by Victor Hugo and Eugène Sue, ‘it is a place that expresses itself through the arts,’ said Professor Leniaud.

Essentially, what we have inherited from Notre-Dame is history and the temporal wisdom that comes with it. We have inherited this through architecture, landscape and nature, literature, the arts, and human rituals. This is what makes Notre-Dame and every cultural heritage so sacred, Professor Leniaud concluded. Cultural heritage is more than a commercial attraction, as it is universally recognised as sacred and worth preserving. As such, it has the potential to unify people and create a space of mutual understanding and respect.

A product of its local culture and history, cultural heritage that has endured across generations not only reflects local identity and values that produced it but also holds something sacred that resonates with people globally. The concept of world heritage, first formalised and institutionalised by UNESCO in 1972, has such ‘outstanding universal value’ that its ownership transcends borders. Notre-Dame is undeniably rooted in French history and culture and has become a symbol of France as a nation, but the global outcry and its reconstruction efforts after the 2019 fire demonstrated the world’s shared responsibility in preserving local cultural heritage for humanity.

6. Cultural Diplomacy and Education for Peace

Cultural heritage sites, as well as international education, can be broadly seen as elements of cultural diplomacy. As explored by Ambassador Paolo Sabbatini of the World Sinology Center, China, cultural diplomacy is a way to create understanding and empathy towards others. In his keynote speech, ‘The Future of Cultural Diplomacy: The Legacy of Marco Polo,’ he looked back at Marco Polo’s journey into the unknown, as he ventured out to Asia in the 13th century and eventually became a messenger between the Mongol Empire and the West, or what we might term a cultural diplomat today. According to Ambassador Sabbatini, everybody can be a cultural diplomat and, in fact, people-to-people diplomacy happens daily. Being a cultural diplomat means much more than representing our culture. It is ‘to study and be aware of things that can make another person happy’, he explained. ‘When we engage in cultural diplomacy, it is not to win or to reason. It is to demonstrate that, after all… we have many more similarities than differences,’ he continued.

Cultural diplomacy, the aggregation of people-to-people diplomacy, can only take place within a liberal world, where people can freely express themselves without fear of censorship, exclusion, or violence. In a world where liberalism is seemingly dying and we have to fight for certain liberties, it is essential to create spaces for dialogue, where such people-to-people diplomacy can take place freely. When other lines of communication are poor, academia can hold space and open channels for discussion of sensitive topics, unbiased and always inquisitive about the other. IAFOR positions itself as an organisation that links academia and people-to-people diplomacy, and it will continue advocating for the internationalisation of higher education in a world that works against it. It endeavours to bring the international, the intercultural, and the interdisciplinary together, creating a convivial space for international engagement and people-to-people diplomacy at our conferences and within the greater IAFOR community.

In today’s more fragmented and heterogeneous world order, cultural diplomacy is more important than ever. On a panel titled ‘Education and Cultural Diplomacy as a Tool for Peace’, moderated by Ambassador Sabbatini, panellists Dr Charlotte Faucher of the University of Bristol, United Kingdom, Professor Frédéric Ramel, Sciences Po, France, and Japanese Ambassador to UNESCO, Takehiro Kano, explored the role of cultural diplomacy and education as a form of soft power that promotes peace. In these times of geopolitical tension, military and security issues are taking precedence over education and culture. Quoting Raymond Aron, the foremost political and social theorist of post-World War II France, Professor Ramel explained that we cannot understand the international system if we limit its evaluation to polarisation, that is, the number of great powers and military expenditure. We also have to think about the heterogeneity of the international system today, resulting from the cleavage between authoritarianism and democracy on the one hand, and between illiberalism and the ‘spirit of democracy’ , the global discourse of de-westernisation, and the narratives of civilisation states, such as Russia, China, India, and Turkey, on the other. It is within this quest of universality that we need cultural diplomacy, Professor Ramel said. Therefore, hard power is not enough. We need soft power, in the form of cultural diplomacy, in order to ‘welcome the other person or the other field, and to be touched by and resonate with the other,’ he explained.

The potential for people to connect with other people has had far more influence than any hard power in determining the relationship between nations, according to Dr Faucher. She explained how people-to-people diplomacy began in the 19th century, long before it was institutionally recognised, when European nations started to form, and non-state actors (teachers, merchants, and migrants) promoted their nations abroad. Migrant communities with their early forms of people-to-people exchange laid the foundations for modern cultural diplomacy, carried out today formally by UNESCO.

Ambassador Paolo Sabbatini of the World Sinology Center, China (left), and Ambassador Takehiro Kano of UNESCO (right).

Ambassador Kano explained that after WWI, European nations realised that even homogeneous systems, such as Europe, required more mutual understanding through science, education, and culture, which eventually led to the creation of the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation (ICIC), the predecessor of UNESCO. ‘Cultural heritage is one successful model of UNESCO’s global cooperation,’ Ambassador Kano stated. According to him, heritage sites that were in danger, like Angkor Wat in Cambodia, the Tombs of Buganda Kings in Uganda, or indeed Notre-Dame, required the international community to work together to preserve or reconstruct them.

However, UNESCO is facing increasing obstacles to its work. In terms of cultural heritage, challenges include disputes over repatriation, cultural appropriation, and overlapping claims of heritage ownership. Some nations try to promote their cultural heritage in a commercially viable way, but, according to Ambassador Kano, ‘sometimes this can go too far, in the case of overtourism, which can have an adverse effect on cultural heritage.’ Business and cultural diplomacy go hand in hand, and according to Professor Ramel, ‘the business of cultural diplomacy can be linked to the evolution of capitalism. A new song, for example, can be the source of growth today.’ Therefore, cultural diplomacy must be employed carefully, as it is ‘closely connected to both war and peace.’

Professor Frédéric Ramel (Sciences Po, France)

Dr Charlotte Faucher (University of Bristol, United Kingdom)

UNESCO also recognises the fragility of multilateralism, seeing how the US has withdrawn twice from the organisation (in the 1980s and 2010s), most recently under the Trump administration, before rejoining under Biden and now reconsidering membership again. Moreover, civil servant diplomats sometimes have a hard time dealing with complex issues by themselves, such as climate change or nuclear power/armament. According to Professor Ramel, they need the help of academia, civil society, or global health institutions. This shows the emergence of a new, multilateral, and multisectoral model of diplomacy, a statement that echoes the discussions carried out at the PCE/PCAH2024 Conference in Paris last year.

In today’s fragmented world, cultural diplomacy offers a way to build empathy, preserve heritage, and foster peace and cooperation. Its future depends on whether formal institutions recognise the role of both state and non-state actors, and whether people realise how important their everyday interactions with others are, especially when they venture into unknown lands, either for educational, cultural, or economic reasons.

7. Conclusion

In times of uncertainty, when geopolitical tensions, economic instability, and disruptive technologies threaten to divide countries and compromise peace, education and culture must defend peace and cooperation. The discussions at PCE/PCAH2025 have shown that while internationalisation, interculturalism, and interdisciplinarity face increasing challenges, academics, artists, and professionals are ready to defend them, especially at times when they may feel that national governments do not properly represent them. Whether through the reconstruction of Notre-Dame as a universal symbol of shared heritage, the daily acts of people-to-people diplomacy inspired by Marco Polo’s legacy, or the repositioning of education with the human at its core through meaningful collaboration across borders and disciplines, the message is clear: rethinking of education and culture is necessary to address the global challenges of today.

UNESCO’s founding vision that peace must be built in the minds of people resonates more than ever today. To address today’s global challenges, we must reinvest in human imagination and in cultural and intellectual exchange. ‘This is why UNESCO continues to advocate for increased investment in education, which is not absolutely obvious now,’ Dr Giannini said. This reminds us of Dr Amir Dhia’s keynote speech at the ACEID/ACP/AGen2025 Conference in Tokyo last March, in which he advocated for innovative new funding for education through multisectoral cooperation, in a time when national governments are turning off the faucet of educational and research funding. IAFOR is committed to continuing this debate on refinancing education, with a plan to discuss this at the BCE/BAMC2025 Conference in Barcelona at the end of September and the IICE/IICAH2026 Conference in Hawaii next January. If we succeed in reimagining education and culture as shared global responsibilities rather than transactional commodities, we can continue to build the bridges necessary for a more peaceful, inclusive, and hopeful world.

From left to right: Milica Papić, Director of the Belgrade Youth Office, Serbia; Giorgio Tenneroni, President of the Municipal Council of Todi, Italy; and Riccardo Travaglini of the General Workers Union, Malta

8. Featured Roundtables

In an attempt to platform youth perspectives and experiences with cultural diplomacy, the PCE/PCAH2025 conference featured a roundtable on ‘Youth and Cultural Diplomacy’ in its extended programme on the first parallel day. Moderated by Ambassador Sabbatini, the panellists Milica Papić, Director of the Belgrade Youth Office, Serbia; Giorgio Tenneroni, President of the Municipal Council of Todi, Italy; and Riccardo Travaglini of the General Workers Union, Malta, first defined the term ‘youth’ and then shared challenges they faced in their respective positions as young local civic leaders, as well as opportunities arising from youth-driven diplomacy. Contrary to the stereotypical narrative that young leaders have a hard time being heard by seasoned cultural diplomats and local politicians, all three of these young diplomats mentioned that the toughest challenge was to motivate youth to participate in civic engagement. According to them, with powerful digital tools such as social media, we need a new approach to civic engagement and participation to attract younger generations and educate them on the importance of people-to-people diplomacy.

The session was an important part of the academic programme that focused on broader questions of rethinking our current systems, institutions, and engagement with each other. Youth cannot be excluded from such discussions, as they are the drivers of reform, bringing innovative ideas and serving as future leaders of our socio-economic, political, and cultural systems. With a well-attended and engaging session, IAFOR recognises the necessity to platform youth voices through our fourth Conference Theme of Leadership, and considers this as a topic to be explored at future conferences.

As part of IAFOR’s capacity-building programme, the conference also offered a roundtable on ‘Senior Academic Leadership’. Moderated by Dr Joseph Haldane, the roundtable featured senior academic leaders Professor Boddington and Professor Hall, who shared their respective decade-long experiences in senior leadership. Confronting issues of sexism, sexual orientation, disciplinary marginalisation, and collaboration in academia, the two speakers agreed that resilience in academic leaders comes from taking care of the people they work with. Rather than focusing on the monetary compensation that comes with the position, creating meaningful connections with people within and across institutions, and a genuine desire to make a difference in the world of academia is necessary for leaders to survive and thrive. The session proved to be engaging and of high interest to participants, many of whom currently struggle with similar challenges in their newly appointed senior positions. Early career academics who aspire to become academic leaders also showed remarkable interest in the session. IAFOR, thus, recognises the importance and the existing demand for intergenerational transfer of knowledge and mentorship, and will consider this session as a blueprint for future capacity-building projects.

8. Cultural Programme

IAFOR conferences are prime spaces to witness people-to-people diplomacy in real time and to appreciate the importance of shared culture and knowledge. With as many as 80 different nationalities present, IAFOR conferences’ networking events and cultural programmes are a manifestation of the theoretical discussions taking place during the plenary and parallel sessions. Venue- and locally specific events are designed not only to provide spaces where participants can gather, connect, and make new contacts within the IAFOR network, but also where delegates can experience the meaning and importance of culture in our lives. The inclusion of such events at a joint conference such as PCE/PCAH2025 is integral to IAFOR’s mission of fostering international, intercultural, and interdisciplinary collaborations, as they provide spaces where attendees from various areas of research can meet and mingle with people from different nations and cultures, beyond their respective disciplines.

Welcome Reception

The Conference Welcome Reception closed out the first day of the plenaries, and was held alongside the Conference Poster Session. An IAFOR conference staple, the Welcome Reception is the embodiment of people-to-people diplomacy, where people from different nationalities, cultures, and non-Native English speakers must muster up the courage to open up to the different ‘other’, without preconceived notions and prejudice. This event is always free for delegates to attend, and provides a relaxed networking space where delegates can become better acquainted with each other. With 80 different nationalities present, the Welcome Reception embodies how diversity can function within a convivial atmosphere of respect and excitement. Participants were able to reconvene with colleagues they met during the opening day’s keynote presentations, converse with poster presenters, and meet new faces at the event. Creating such spaces for delegates to network and form long-lasting connections within our conference programme is essential to our conference planning.

Conference Dinner

The Conference Dinner provides an exclusive event within the conference programme where plenary speakers, IAFOR Executives, and VIP guests can partake in more in-depth conversations with the participants. IAFOR Conference Dinners are always held at spectacular venues, offering high-quality dining, unique cultural experiences, and a welcoming platform for attendees to connect over one of the most beloved vessels of intercultural exchange: good food paired with great conversation.

Food, much like architecture or literature, is an entry point into the soul of a culture. Cuisine becomes a cultural practice when shared as a meal with others. As UNESCO recognised in 2010 when the organisation inscribed the ‘gastronomic meal of the French’ on the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity list, French cuisine is one of the most recognisable gastronomic cultures in the world. Much like physical locations such as Notre-Dame, French cuisine is undeniably French, yet it is replicated, re-interpreted, and enjoyed the world over. From boulangeries to brasseries and Michelin-star restaurants, French gastronomy remains a cultural heritage that unites the local and the global.

The Conference Dinner for our Paris Conference Programme returned to Bofinger Brasserie, praised as one of the most beautiful brasseries, or breweries, in Paris for over 150 years. Established in 1864, Bofinger was the first to introduce beer to the city of Paris and has preserved its historic interiors over time. Delegates were able to sample the restaurant’s traditional French fare and experience a facet of Paris’ storied food culture first-hand, while engaging in discussions around the conference’s academic programme, perhaps unwittingly performing the people-to-people diplomacy they had heard about during the day.

Cultural Presentation: The Story and Songs of Paris’ ‘Barbara’

The Paris programme’s Cultural Presentation featured a biographical musical performance by local singer-songwriter, Sophie Leliwa, re-telling the life of beloved Parisian folk singer, songwriter, and actress, ‘Barbara’. Barbara, the stage name of Monique Andrée Serf, was a pioneering cabaretière in the 1950s and 60s in Paris, and was also known as La Chanteuse de minuit — 'the midnight singer'. Accompanied by fellow musicians Bruno Rougevin-Baville & Nathan Kuperminc, Ms Leliwa told the story of Barbara’s life through some of her most famous songs, such as ‘Ma plus belle histoire d'amour’ (1966) and ‘L'aigle noir’ (1970), allowing delegates to re-live her life through song.

This performance also highlighted the enduring cultural significance of la chanson française, a genre inscribed in UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. French chansons are not only an artistic expression of poetry and music, and, of course, entertainment, but also a reflection of collective memory, identity, and social history. Especially in the case of Barbara, the musical repertoire performed during the conference offered a shared cultural understanding of women’s lives in postwar Europe. Through story and song, Ms Leliwa told the life story of Barbara, whose own lyrics speak of sexual abuse at a young age, and dark times of a Jewish girl in hiding during WWII. These are themes that continue to resonate with people today, and represent a shared memory and understanding of violence. The inclusion of such a presentation in the programme was, therefore, more than mere entertainment. It recognised the important role of culture in our lives, and of the belief that cultural expressions, whether local or global, belong to all of us.

Subscribe and Stay Informed

Receive key insights directly to your inbox.

Stay informed of the latest developments in academia.

100% free to read, download and share.

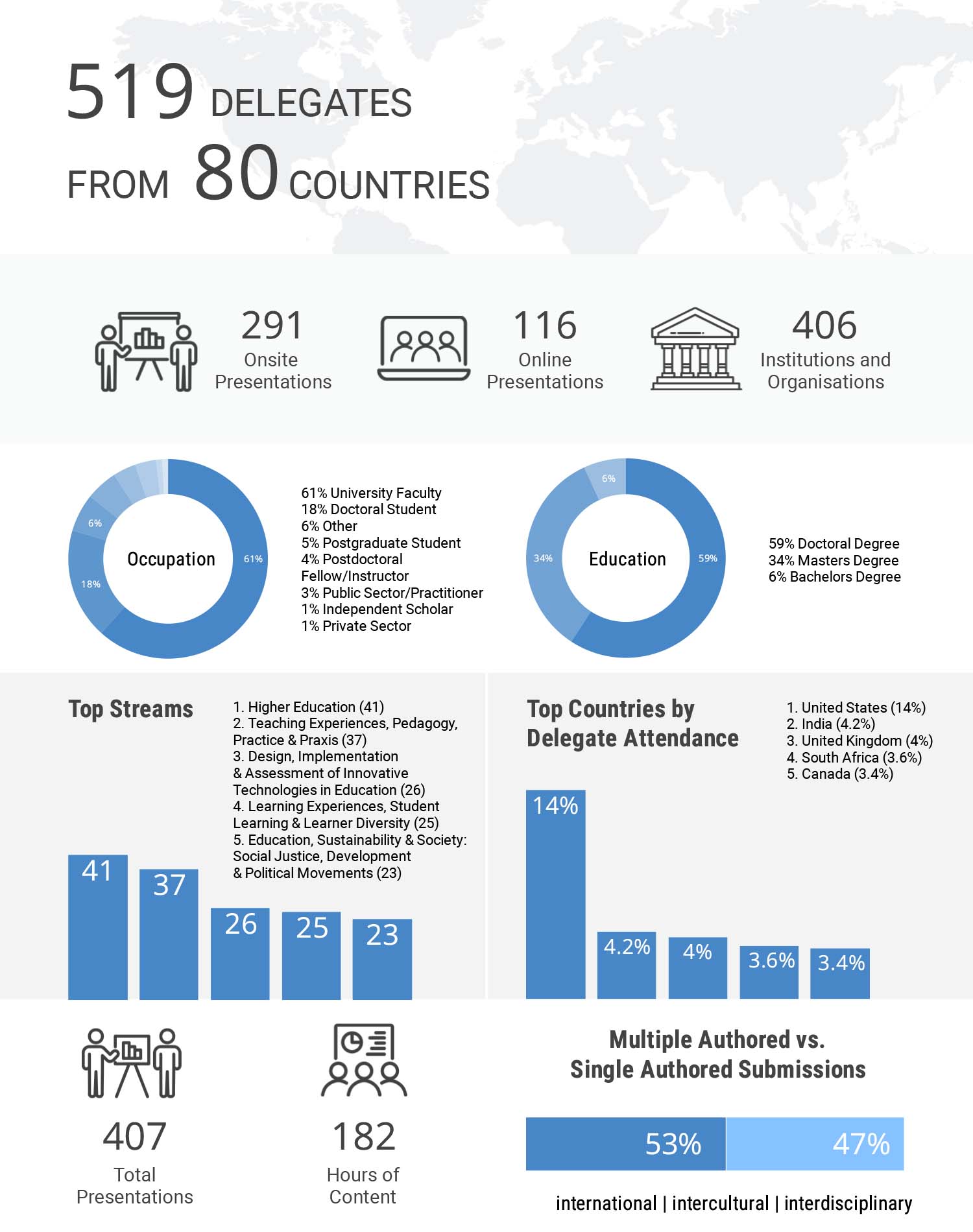

Key Statistics

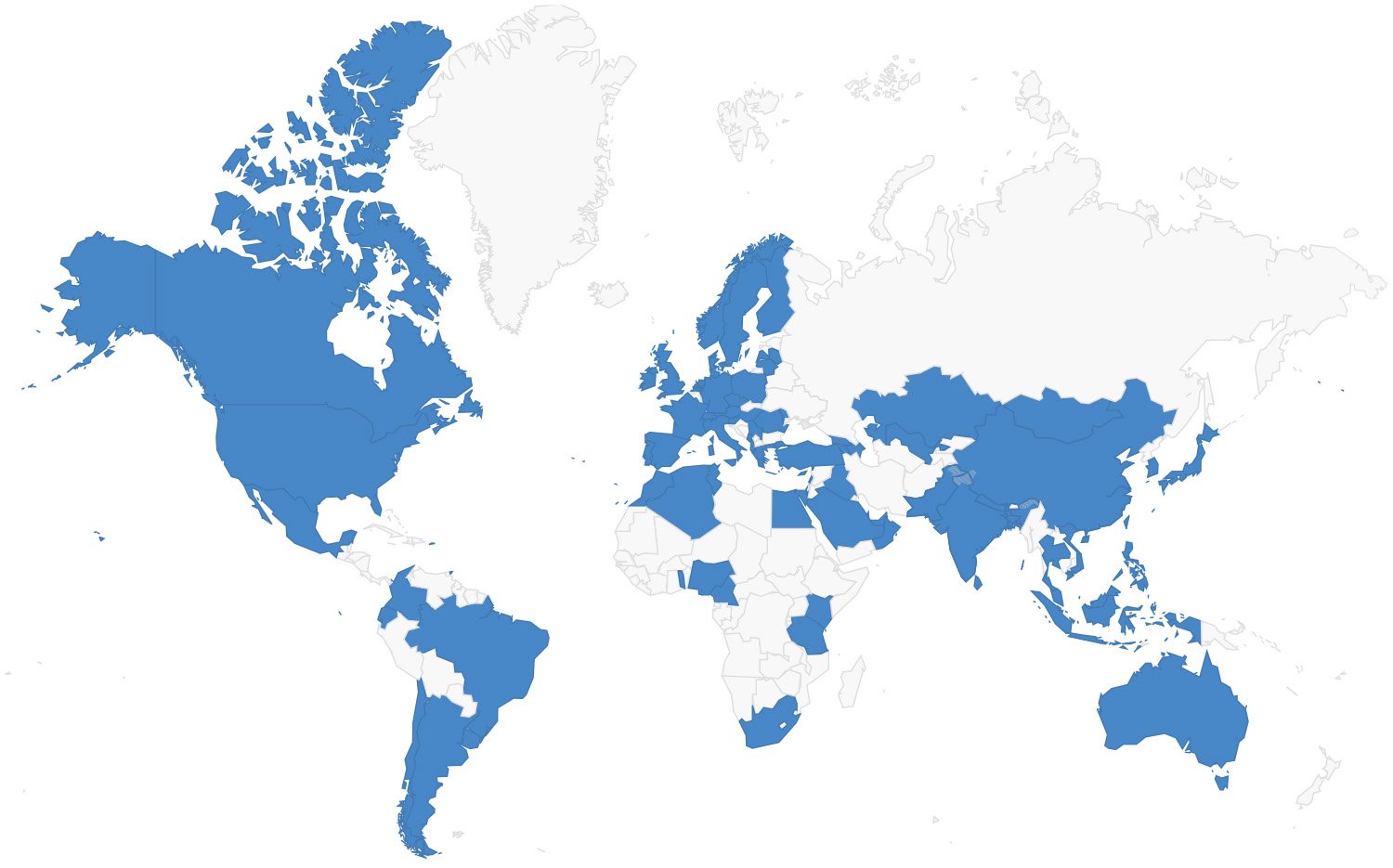

Delegate World Map & Country Breakdown

Total Number of Attendees: 519

Total Number of Countries Represented: 80

| Country | Count |

|---|---|

| United States | 74 |

| India | 24 |

| United Kingdom | 22 |

| South Africa | 19 |

| Canada | 18 |

| Brazil | 16 |

| China | 16 |

| Philippines | 14 |

| Hong Kong | 12 |

| Japan | 12 |

| Singapore | 12 |

| Thailand | 12 |

| Turkey | 12 |

| Germany | 11 |

| France | 10 |

| Kazakhstan | 10 |

| Taiwan | 10 |

| Australia | 9 |

| Mexico | 9 |

| United Arab Emirates | 9 |

| Oman | 7 |

| Qatar | 7 |

| Saudi Arabia | 7 |

| South Korea | 7 |

| Spain | 7 |

| Georgia | 6 |

| Indonesia | 6 |

| Italy | 6 |

| Portugal | 6 |

| Serbia | 6 |

| Vietnam | 6 |

| Argentina | 5 |

| Colombia | 5 |

| Greece | 5 |

| Hungary | 5 |

| Malaysia | 5 |

| Morocco | 5 |

| Nigeria | 5 |

| Czech Republic | 4 |

| Israel | 4 |

| Country | Count |

|---|---|

| Lebanon | 4 |

| Pakistan | 4 |

| Tanzania | 4 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 4 |

| Egypt | 3 |

| Mongolia | 3 |

| Poland | 3 |

| Romania | 3 |

| Austria | 2 |

| Azerbaijan | 2 |

| Bangladesh | 2 |

| Cameroon | 2 |

| Ecuador | 2 |

| Finland | 2 |

| Iraq | 2 |

| Ireland | 2 |

| Lithuania | 2 |

| Montenegro | 2 |

| Sweden | 2 |

| Switzerland | 2 |

| Togo | 2 |

| Tunisia | 2 |

| Albania | 1 |

| Algeria | 1 |

| Armenia | 1 |

| Chile | 1 |

| Cyprus | 1 |

| Denmark | 1 |

| Kenya | 1 |

| Latvia | 1 |

| Macau | 1 |

| Moldova | 1 |

| Nepal | 1 |

| Netherlands | 1 |

| Norway | 1 |

| Puerto Rico | 1 |

| Slovenia | 1 |

| Sri Lanka | 1 |

| Uruguay | 1 |

| Uzbekistan | 1 |

Subscribe and Stay Informed

Receive key insights directly to your inbox.

Stay informed of the latest developments in academia.

100% free to read, download and share.