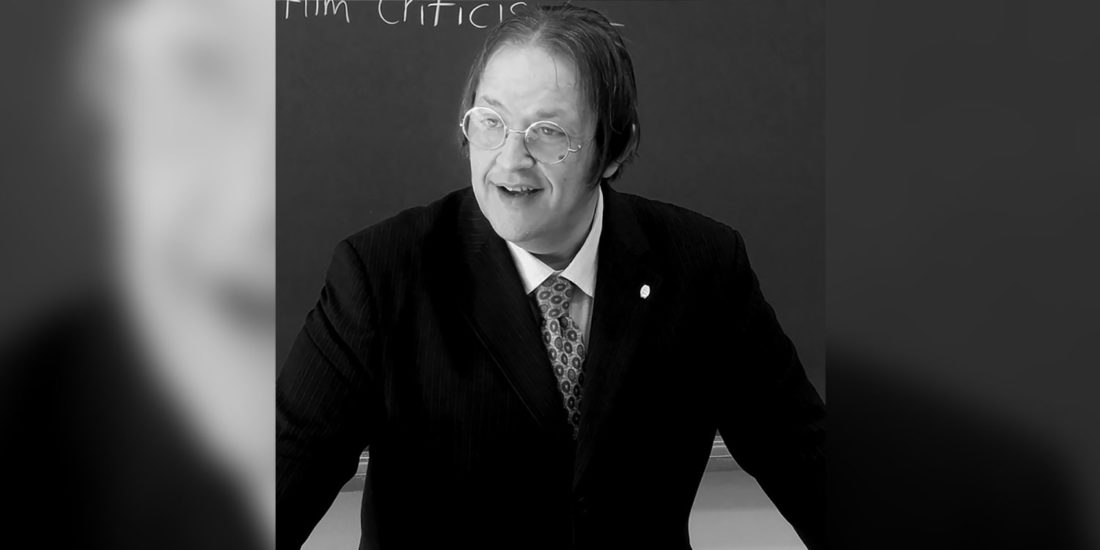

Dr Paul Spicer

MediAsia2016 Conference Co-Chair and Featured Speaker

Hiroshima Jougakuin University, Japan

Dr Paul Spicer, Conference Co-Chair and Featured Speaker for The Asian Conference on Media, Communication & Film 2016 (MediAsia2016), will focus on the Taisho Democracy Era (1912-1926) in Japanese film history by discussing the volatile state of contemporary Japanese politics, and how the film industry reacted to it. His full abstract is available to read below.

Dr Paul Spicer is currently an Associate Professor at Hiroshima Jougakuin University in the beautiful city of Hiroshima. He was previously employed by the University of Portsmouth as a lecturer within the School of Creative Arts, Film and Media, where he co-ordinated the courses Japanese Cinema and Culture, and East Asian Cinema. In 2001 he decided to return to education, and began a degree programme at Portsmouth. He successfully graduated in 2005 with a BSc(1st Class Hons) in Entertainment Technology. In 2007, he began work on his doctoral thesis entitled ‘The Films of Kenji Mizoguchi: Authorship and Vernacular Style’. He completed his thesis in August 2011, and successfully sat his Viva Voce at the University of Portsmouth the same year. Dr Spicer’s research lies primarily in the area of film and cultural studies, and his current work focuses upon the relationship between film and Japanese socio/political issues between 1965-1975.

Featured Presentation: Political Turmoil, Institutional Mistrust, and the Tendency Film Contemporary Representations of Political Ideology in Suzuki’s Naniga Kanojo wo So Sasetanoka (What Made Her Do It?) (1930)

Japan in the 1920s was an exciting and somewhat unusual period that witnessed the people’s fight for political and social freedom. Known commonly as the Taisho Democracy Era (1912-1926), it was a confused and volatile era of change, filled with social and political unrest.

These changes were not confined to Japan as throughout the world, empires fell, societies burned, and markets crashed. Despite the often violent nature of these events, the Japanese saw them as victories for both democracy, and the people. In addition, society was introduced to new ways of thinking, as Japanese intellectuals found inspiration in the writing of Gorky, Plekhanov and Marx. A steady increase in the influence of foreign political thought, particularly communism, can be witnessed through the literature and art of the era, and where writers such as Kaoru Osanai and Saneatsu Mushanokoji frankly expressed left-wing views in their work.

These topics were also explored by the Japanese film industry. Directors such as Daisuke Ito, Masahiro Makino, Tomu Uchida and even the celebrated ‘Golden Age’ director, Kenji Mizoguchi, crafted politically charged work which was sympathetic to the left. They skilfully critiqued the contemporary political system, highlighting the plight and harsh reality of life for many ordinary Japanese people who had become disillusioned with reports of institutional corruption. Tales of unfair practices went right to the top of both business and government and saw the country’s Prime Minister, Hara (celebrated as the Common Prime Minister), and the financier, Zenjiro Yasuda, both ‘accused’ of corruption. The people felt that the trust that they had afforded these public figures had been betrayed, although their demise (both Hara and Yasuda were assassinated in 1921), was met with shock. Hara was stabbed by right-wing sympathiser, Nakaoka Konichi, and Yasuda, murdered by the ultra-nationalist group Heigo Asahi, after he refused to back them financially. Despite both figures’ desire for change, the public disdain felt towards them, and others in similar positions, were seized upon by a shrewd military campaign which, throughout the 1920s, steadily seized political and social control through a series of coup d’états.

The films that represent this period fall into two distinct categories. The escapist fantasy, which relied on the recognisable literature of jidai geki (period drama); and the tendency film, which was a realistic and harsh portrayal of modern life, attempting to offer solutions to the woeful economic situation in Japan. As the name suggests, the film’s themes were a reaction to a specific social tendency. Set on the political backdrop of this era, many tendency films were produced. Directors explicitly addressed the poor societal conditions forced upon the people, and highlighted the corruption which, they argued, had caused it.

This paper will focus on this period in Japanese film history by discussing the volatile state of contemporary Japanese politics, and how the film industry reacted to it. Despite the military being in control by the late 1920s, and cinematic restrictions imposed a little later, many films that were produced had extreme political views. One film in particular, Shigeyoshi Suzuki’s 1930 tendency piece Naniga Kanojo wo so Sasetanoka (What Made Her Do It?), is a stellar example. Produced by Teikoku Kinema Engei, and adapted by Suzuki from a play by Seikichi Fujimori, the film was made on the cusp of the change from a democratic to a militaristic nationalist society. The film explores the plight of the everyday people in 1920s Japan, focusing upon the unfair and corrupt systems of authority which they have to endure. In addition to the political context of the film, the presentation will visually analyse Suzuki’s methods, exploring how, through stark imagery, he promotes a distinct and unashamed left-wing ideology.